Culture Shock and Adaptation

Culture shock

Kalervo Oberg was the first anthropologist to use the expression “culture shock” to describe the stress and disorientation experienced by individuals adjusting to a new culture. Culture shock occurs when people leave familiar surroundings and plunge into an unknown environment. It results from the loss of the signs and landmarks we use to guide our daily actions. Moving to a new community is a fascinating challenge, but can cause a great deal of stress and anxiety.

When we confront a new culture, all the presuppositions and clues we use to guide us in daily life disappear. Culture regulates every aspect of our lives: when to shake hands, what to say when meeting people, when and how much to leave as a tip in a bar or restaurant, how to shop, when to accept or turn down invitations, and more. The simplest everyday gestures need to be relearned in the new culture. The values and beliefs of the host society may differ from or contradict those of our home country. And in moving to a new country, we must entirely rebuild our social circle and make new contacts, a process that takes a great deal of time and energy.

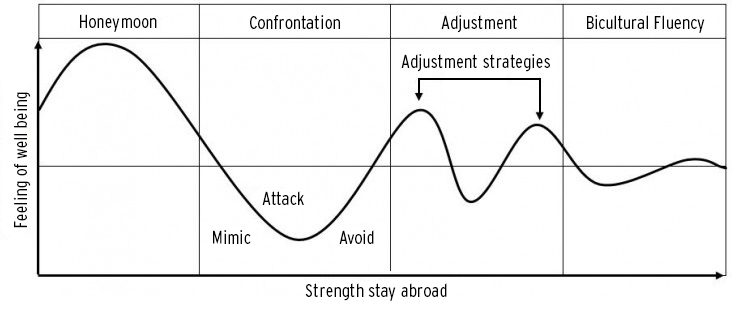

Cultural shock can be diagrammed as a U-curve with 4 main stages often described as the honeymoon, confrontation, adjustment and bicultural fluency. These stages often blend and overlap, and vary in length for different people.

Honeymoon

In the days and weeks before and after your arrival in Québec, you may experience feelings of euphoria and excitement, and will you have many expectations about your stay. Upon arriving in your new country, everything is new and exotic, and seems perfect. You have a very positive attitude and are eager to see and do everything and try new things.

Crisis or Conflict

This stage normally coincides with the start of one’s routine—often the start of classes—and marks the switch from the “tourism experience” phase to the “stay abroad” phase. It is a period of disillusionment, when the differences between Québec and your home country become more apparent. You may idealize the country you just left and constantly criticize Québec. You feel disoriented by the loss of familiar cues and may have difficulty knowing how to behave effectively. Common symptoms of this phase include feelings of confusion, frustration, powerlessness, isolation, nostalgia and homesickness, boredom, loss of appetite, irritability, stress, hostility toward the host country and its inhabitants, fatigue, and headaches.

Adjustment

Adjustment is gradual and requires time and patience. Little by little, you learn to accept—without judgment—Québec’s culture, people, customs, and values. You eventually start to develop a social network and feel less isolated, and as you become more familiar with societal practices and customs, you feel less powerless and more capable. You find a balance between the values of your home country and those of the host country. The new gradually becomes normal.

Bicultural Fluency

Becoming biculturally fluent is a long process that can take several years. You know you’ve achieved it when you are just as at ease in your host culture as you are in your own. You understand your host culture and can explain it to newcomers, and if you leave, you will take part of the host culture with you.

Overcoming Culture Shock

There is no magic solution for dealing with culture shock. Everyone has to find their own balance between the values of their home country and those of the host country. But simply knowing what culture shock is and being able to name your feelings is a relief. The best strategies are to give yourself time to adjust, resist the temptation to withdraw into yourself, and lower the expectations you have for yourself and the host country.

Ways to Reduce the Effects of Culture Shock

1. Socialize with Quebecers.

Ask questions to learn more about the host country. Bureau de la vie étudiante coordinates many welcome activities offered each semester as well as a buddy program that can help you meet Quebecers.

2. Avoid isolation: go out, meet people, take part in activities.

Living in residence, at least for your first few semesters, can be a good way to avoid isolation.

3. Be curious: read and find out as much as possible about Québec.

4. Be tolerant, open-minded, and flexible.

5. Avoid hasty judgments.

6. Talk about your experience with someone who has experienced cultural adjustment before. You can also meet with the foreign student advisors at Bureau de la vie étudiante by calling 418-656-2765.

7. Take French classes.

If French is not your first language, don’t hesitate to enroll in French Foreign Language courses at Université Laval’s École de langues so that you can communicate more effectively with your professors and classmates.

8. Keep engaging in the sports and recreation activities you enjoyed in your country.

9. Get involved in your new community: do volunteer work or join a student association, for example.

10. Stay in touch with your home country, family, and friends.

11. And above all: be patient with yourself and others.

Always keep in mind that adapting to change is a gradual process that does not happen overnight. Adaptation requires that you adjust your everyday behavior and emotional reactions. It also requires a great deal of learning. You may very well discover abilities you never knew you had. Remember that adaptation is a normal and positive process!

Sources

“Du choc culturel à l’intégration,” Sonja Susnjar. Article published in Bulletin Vies-à-vies, Vol. 4, No.5, April 1992, Université de Montréal.